Our recent trip to Niagara Falls was not for “the honeymoon we never had,” but to learn more about my only Canadian ancestor—GGG Grandfather Captain Robert Henry Dee, Esquire—who immigrated to Upper Canada (now Ontario) c. 1819. Robert Henry was born c. 1788 to Thomas and Anne Dee, He was baptized on 2 April 1788 in Weyhill, Hampshire County on the southern coast of England.[1]

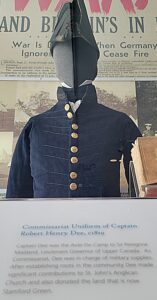

Captain Dee served as the Deputy Commissariat in the Napoleonic Wars for fourteen years. “As Commissariat, Captain Dee was in charge of military supplies,” responsible for overseeing military food and equipment.”[2] He was also aide-de-Camp, or personal assistant, to General Sir Peregrine Maitland. They served together in the Peninsular War and possibly at the Battle of Waterloo.[3] Captain Dee married Elizabeth Ottley (1796-1876) on 31 March 1819 at St. Cuthbert’s Church, Thetford, Norfolk, England.[4] She was the daughter of Matthew and Elisabeth (Hill) Ottley.[5] One year later they followed Maitland to Upper Canada, now Ontario.

In 1818 General Maitland was summoned to Stamford, Upper Canada to serve as lieutenant governor until 1828.[6] As aide-de-camp to Maitland, Captain Dee joined him about 1819. On 2 November 1824 he purchased the 100-acre lot no. 56 on the Portage Road “that was part of one of John Burch’s Crown Grants.”[7] He then donated 3.5 acres off “the western extremity of the Dee farm” for the Stamford Green, the only village green in Canada. The Dee family kept this land open “for the benefit and enjoyment of the public,” from 1821 until 1909. Stamford Green is now controlled by a Board of Trustees.[8]

On 20 September 1820 Mr. R. H. Dee also donated the land for the construction of the Old St. John’s Anglican Church. Building began in 1821, and it was consecrated in 1825.[9] In 1827 he donated more land to the church for a church yard and burial ground.[10] Because of the donations of land, an additional 25 pounds, and a “wooden armchair used in the vestries,” a window was dedicated to “commemorate the liberality of Robert Henry Dee and Elizabeth Dee to this Church.”[11] An historical marker also commemorates his “additional financial support and gifts of land and furnishings” to the church.[12]

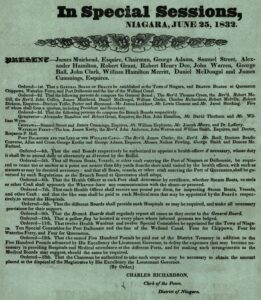

After his military career, Robert Henry Dee Esquire remained involved in the community. On 23 September 1822, Robert and six others joined the Dalhousie [Masonic] Lodge in Niagara.[13] According to an 1824 document signed by four of the members, including R. H. Dee, the lodge closed “from want of funds till more advantageous circumstances arise.”[14] On 25 June 1832, Robert Henry Dee was present at a Special Session that created a General Board of Health in the Town of Niagara. This Order “coincided with the cholera epidemic of 1832 and was likely created in an attempt to control the spread of the disease.”[15]

Robert Henry was possibly in poor health, as he also wrote his will three days later on 28 June 1832.[16] In October 1833, he also wrote that he was not well.[17] He died at the young age of 46 on 11 November 1833 at Stamford. Robert left seven children under age fourteen with his wife, Elizabeth, who was two months pregnant. He was buried in the family plot at the Church of St. John the Evangelist. Also buried there are Elizabeth (d. 1876), father-in-law, Matthew Ottley (d. 1845), and children Frances Ann, Harriet Martha, and John Matthew, MD.[18]

The house which Captain Dee built c. 1824, now 3252 Portage Road, was later enlarged.[19] All eight of Robert and Elizabeth’s children were likely born in Stamford: William Hornblow (c. 1820-1875), my GG grandfather; Francis Ottley (1821-1892); Henry Ontario (1823-1904); Thomas Wicken (1825-1897), who married Julia Hamilton from Niagara on the Lake and likely introduced William to his future wife in Wisconsin; Frances Ann (1828-1900); Robert Hill (1829-1908); Harriet Martha (1832-1909); and John Matthew, MD (1834-1913), born just seven months after his father’s death.

While walking around this property and photographing the house, I was lucky enough to meet Bev, the home’s current owner. Because she was leaving, we exchanged business cards and promised to email each other. Three days later, I received an email from her husband, Steven, sorry that we missed each other. He also invited us back to help celebrate the 200th “birthday” of the Dee house this summer. As they have also been researching this family, I sent him my Robert Henry Dee family research. Although not blood relatives, we share a family, and are now house relatives.

[1] “England, Hampshire Bishop’s Transcripts 1680-1892,” database, FamilySearch, Robert Henry Dee, son of Thomas and Anne Dee, Weyhill.

[2] Also, “3227 Portage Rd. Originally Built by Captain Robert H. Dee,” Historic Niagara Collections, photograph and description. For fourteen years, see Land Petitions of Upper Canada, 1763-1865, Robert Henry Dee, Stanford, 1829, vol. 159, Bundle D-16, Petition no. 20, RG1 L3, microfilm C-1876, digital images 152-155; Library and Archives of Canada.

[3] “Commissariat Uniform of Captain Robert Henry Dee, c 1819,” sign describing Dee-Maitland relationship, Niagara Falls Museum, Niagara Falls, Ontario Canada.

[4] “England Select Marriages, 1538-1973,” digital images, Ancestry, Norfolk Church of England Registers, Dee-Ottley, 31 March 1819; Norfolk Record Office, Norwich, Norfolk, England.

[5] “England Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975,” transcript, Ancestry, Elisabeth Ottley, b. 5 Oct 1796, bap. 30 Oct 1796, parents Matthew and Elisabeth Ottley.

[6] George A. Seibel, “Stamford Green,” The Niagara Portage Road: A History of the Portage on the West Bank of the Niagara River (City of Niagara Falls, Canada: 1990), 265.

[7] George A. Seibel, “Stamford Green,” The Niagara Portage Road: A History of the Portage on the West Bank of the Niagara River (City of Niagara Falls, Canada: 1990), 265. Also, “3227 Portage Rd. Originally Built by Captain Robert H. Dee,” Historic Niagara Collections, photograph and description. Also, Stamford Twp., Welland Co. Deeds, Old Series, 1796-1832, A:332-33, no. 6643, microfilm GS2893; Archives of Ontario, Toronto.

[8] George A. Seibel, “Stamford Green,” The Niagara Portage Road: A History of the Portage on the West Bank of the Niagara River (City of Niagara Falls, Canada: 1990), 265.

[9] Frank Goulding, 150 Years of Christian Witness, 1820-1970: Church of St. John The Evangelist (Stamford, 1970), 22-23, deed p. 26. Also, Donna M. Campbell, Church of St. John the Evangelist (Stamford) (Ontario, Canada: Ontario Genealogical society, undated), 1.

[10] Stamford, Niagara District, instrument no. 7353, Robert Henry Dee to Sir Peregrin Maitland for the Church of England church yard and burial ground, FHL microfilm GS 2893. Also, Stamford Twp., Welland Co., Old Series, 1796-1832, A: pp cut off, no. 7353, microfilm GS2893; Archives of Ontario, Toronto.

[11] Frank Goulding, 150 Years of Christian Witness, 1820-1970: Church of St. John The Evangelist (Stamford, 1970), 22, 28, 34.

[12] Ontario Heritage Foundation Ministry of Citizenship and Culture, “Church of St. John the Evangelist” marker, Portage Road, Stamford.

[13] “England, United Grand Lodge of England Freemason Membership Registers, 1751-1921,” registry image, Ancestry, Robert Henry Dee, Esquire, joined 23 Sep 1822, p. 20. These members were “Erased by Grand Lodge 3 Sep 1864.”

[14] Janet Carnochan, “Freemasons,” History of Niagara (In Part) (Toronto: William Briggs, 1914), 123.

[15] “Order to Create a General Board of Health I the Town of Niagara, June 25, 1832: Brock University Special Collections & Archives,” digital image, Our Ontario, Present—Robert Henry Dee.

[16] Lincoln Co. Surrogate Court estate files, RG 22-234, alphabetically filed, Robert Henry Dee will, 28 Jun 1832; FHL microfilm MS 8409; Ontario Archives

[17] Land Petitions of Upper Canada, 1763-1865, Robert Henry Dee, Stanford, 1829, vol. 160, Bundle D-18, Petition no. 50, RG1 L3, microfilm C-1877, digital images 188-190; Library and Archives of Canada.

[18] Donna M. Campbell, “Cemetery Transcriptions,” Church of St. John the Evangelist (Stamford) (Ontario, Canada: Ontario Genealogical society, undated), 2.

[19] “3227 Portage Rd. Originally Built by Captain Robert H. Dee,” Historic Niagara Collections, photograph and description.