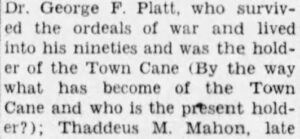

In September 1956 the Public Opinion asked this question when reminiscing about “Dr. George F. Platt, who survived the ordeals of war and lived into his nineties and was the holder of the Town Cane (By the way what has become of the Town Cane and who is the present holder?)”[i] No subsequent responses were noted by the newspaper.

The Downtown Business Council of Chambersburg posed the same question on Facebook in 2023: “What happened to the town cane? Has it vanished like the Hope Diamond?”[ii] None of the twenty-three comments provided a clue to the location of either Town Cane. To date, neither Town Cane has been located.[iii] If you know the whereabouts of either Town Cane, please contact Pam Anderson at [email protected].

It’s been almost 100 years since the tradition began in Franklin County—and over seventy-five years since both canes disappeared: Chambersburg’s in 1941 and Waynesboro’s in 1946. I’ve asked many people & organizations about the canes:

- Pat Fleagle & Waynesboro Historical Society

- Franklin County & Washington County Historical Societies

- Todd Dorsett, Antietam Historical Association

- Preserving our Heritage Archives Museum

- Heather Wade, Franklin County Archivist

- Pete Lagiovani, former Chambersburg Mayor

- Jeffrey M. Stonehill, current Chambersburg Borough Manager

- Kathy Leedy, former P.O. staff writer & Chambersburg Borough Council

- Hurley, Kohler, & Ocker Auctioneers

- Jessica Walker, Wilson College Archivist

- Sam Worley, former Franklin County Commissioner

I also have done five presentations on the Town Canes:

- Franklin County Visitors Bureau

- Rotary Club of Waynesboro

- Franklin County Historical Society

- Waynesboro Lions Club

- Rotary Club of Chambersburg

Other presentations are scheduled. If your organization would like a 20-minute presentation on Franklin County’s Town Canes, contact me.

If you know the whereabouts or have any information on our Town Canes, please contact me at [email protected].

[i] “The Forum of Public Opinion,” Public Opinion, 26 Sep 1956, p. 24, col. 2.

[ii] “Downtown Business Council of Chambersburg: Town Cane,” Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/profile/100064903203617/search/?q=Town%20Cane).

[iii] Negative searches for Town Canes at the Franklin County Historical Society; also 2023 emails to the following: Kathy Leedy, former Public Opinion staff writer and Chambersburg Borough Council member (15 May), Patrick Fleagle, Waynesboro Historical Society (15 May), Heather Wade, Franklin County Archivist (16 May), Peter Lagiovani, former mayor (18 May), Jeffrey M. Stonehill via Cindy Harr, Chambersburg Borough Manager (18 May), John Kohler, Gateway Gallery Auction (18 May), Carl Ocker, Kenny’s Auction (18 May), and Jessica Walker, Wilson College Archivist (19 July).